Bootstrapping in the Valley of Death

29 Nov 2013 by Ash RoughaniEditor's Note: We haven't blogged in a long time. That's because it hasn't been a priority. After all, ideas are only as good as the number of people influenced by them. And without a substantial readership base, it wasn't worth the time to share our thoughts with the world. But we recognize a major trade-off resulted: namely, we lost our voice and the opportunity to share our insights with those of you interested in what we're doing. So in the coming weeks, look for that voice to return and brace yourself for a fresh perspective in the civic innovation space, along with some authentic candor.

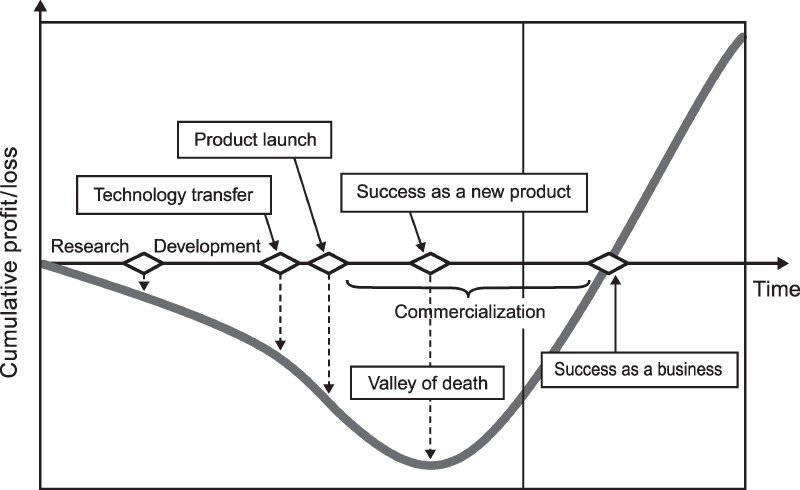

It almost goes without saying that new ventures fail for one of two reasons: either they run out of (1) money, or (2) time. In the world of entrepreneurship, the period prior to a firm achieving profitability is known as the Valley of Death.

Regardless of whether or not a startup is capitalized early on, it must eventually generate sufficient income to cover its costs in order to become financially sustainable. In the case of Public Innovation, we've received zero funding in the 17 months we've been doing our thing. That is, we've been 100 percent bootstrapped (a.k.a. self-funded).

Guy Kawasaki discusses the value of bootsrapping on his blog and some associated strategies. Our reasons are simpler, however. Plain and simple, we weren't sure about the path we wanted to pursue, much less the specific business model we would eventually develop. All we knew early on is that Sacramento is ripe for a more innovative public and social sector.

Bootstrapping is a great way to manage ambiguity. Rather than being accountable to investors for specific deliverables at pre-determined intervals, we were able to take a more inductive approach to developing a plan on which we know we're capable of delivering. And our only deadlines were self-imposed, allowing us to take as much time as we needed.

But bootstrapping comes with a serious price tag. We've essentially established an organization and pursued a comprehensive set of activities without requiring revenue to cover our costs. In other words, we've given away our services and created a public expectation that we'll continue to do so. And the personal sacrifices have not been insignificant.

Creating Value in a Transactional World

Now that we've published our business plan, it's time to sell. Yet, we'd prefer to focus on creating value. Sacramento is a transactional place and there's no immediate economic benefit to be had by investing in Public Innovation. Similarly, waiting for foundation money to drop down from the heavens is a long shot.

It's one thing to identify an unmet need; quite another to find paying customers.

The Art of Sequencing

In recent weeks, an immediate opportunity to launch an incubator program for social entrepreneurs has presented itself. If we went forward with it, the program would be the first of its kind in Sacramento. And it's also a revenue opportunity for us. But the major challenge is the order in which we ought to pursue such opportunities. This is the art of sequencing.

It only makes sense that we demonstrate some progress in the fundraising space prior to recruiting aspiring changemakers to help them develop their own social enterprises. There are also civic technology earned income opportunities, but those come with lengthy procurement cycles and we'd likely need to compete with better-positioned companies. Last but not least, there's substantial infrastructure we still need to build to streamline our lean operation and other important organizational development activities to set ourselves up for success.

The reality we're dealing with is that most people don't value the risks entrepreneurs make. Just as true, is the fact that most new ventures fail. Even social entrepreneurs deal with grief. We'll do all we can to prevent ourselves from flying blind, but the bottom line is we need buy-in from influencers who can evangelize on our behalf and connect us to potential funders.